Well, that was quick. By Wednesday morning, just a few days after a demonstration Saturday over the death of George Floyd while in the custody of Minneapolis police suddenly turned violent, downtown looked eerily neat and quiet.

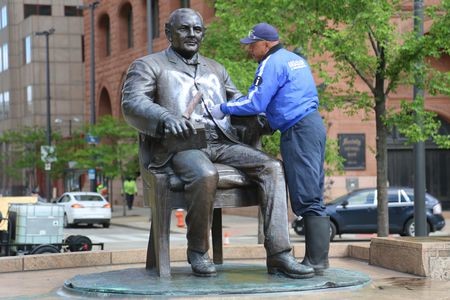

Shattered glass had been swept up. Graffiti had been scrubbed off the bronze statue of early 20th century mayor Tom Johnson in Public Square. Damaged storefronts and restaurants sported fresh, street-level facades of plywood.

Peaceful protests on Saturday, May 30, 2020 in Cleveland turned violent overnight as protesters broke windows in businesses throughout downtown. Sunday morning people were cleaning up the glass and boarding up smashed windows.

Developers and community development pros said that downtown’s renaissance will likely resume after the coronavirus pandemic runs its course. The question is whether Cleveland and other cities can address the structural racism that led to George Floyd’s death.

So far, they haven’t.

As Cleveland and other cities turned their downtowns into centers of entertainment, tourism and residential development over the past 40 years, they failed to address persistent poverty among minorities, particularly blacks.

Such failures include Minneapolis, vaunted until now as a paragon of regionalism and good city planning.

Will George Floyd’s death under the knee of a cop — captured in sickening detail in a cellphone video that went viral — provide a tipping point in awareness and the impetus for a new way of thinking about cities, and a new civil rights era?

Justin Bibb of Cleveland, the chief strategy officer for Urbanova, a Spokane, Washington tech startup focused on improving health, safety and sustainability in cities, fervently hopes so.

Justin Bibb, who grew up in Cleveland’s Mt. Pleasant neighborhood, is founder of Cleveland Can’t Wait, a nonprofit focused on revitalizing Cleveland through civic tech and entrepreneurship.

His wish is personal as well as professional. Bibb is a young executive with a stellar resume, a deep commitment to the future of cities, and an extensive record of civic engagement in Cleveland.

Despite his status, he was afraid to leave his downtown Cleveland apartment during the post-riot curfew simply because he is black.

“I have no groceries at home and I’m terrified of getting arrested if I leave,” he said in a tweet Monday, sharing his fear with the world.

Bibb’s story offers a glimpse of the anxiety felt in America by black and brown men who dread encounters with police, no matter how much success they achieve.

But policing is only part of the problem. Less visible systems, from redlining to predatory lending, high rates of incarceration, poor education and poor access to health care, have vastly limited the number of minorities able to climb up and out.

Mark Joseph, an associate professor of community development at Case Western Reserve University, said in a memorable public forum several years ago at Cleveland State University that it took 500 years to create America’s racial dilemma, rooted in black chattel slavery and violent conquest of native inhabitants, and it will take another 500 years to fix it.

“I was overly optimistic when I said that,’’ Joseph said this week when asked about his comment. “Are we making progress toward black people in America having the same value as other people? No, we are not.”

The causes of the demonstrations over George Floyd’s death include the heavily disproportionate impact of the coronavirus pandemic on minority communities, plus a pent-up sense of futility over police killings of unarmed blacks, Joseph said.

Another trigger is the disparity between city neighborhoods experiencing an influx of new wealth amid persistent poverty nearby.

“The people of color who have lived in these barely-working cities for generations are realizing: ‘It’s not my city anymore, so why not take out my rage on it?’ ” Joseph said.

The violence unleashed in Cleveland Saturday was wrong, and self-defeating. But it would be equally wrong to ignore what caused it. The damage highlighted symbolic spaces and structures that embody imbalances of class and race.

Protestors smashed windows on the Justice Center, the hulking Brutalist-style monolith where nine inmates died in an 11-month period in 2018 and 2019 from causes including suicide and drug overdoses that went ignored.

The entrance to the Colonial Arcade in downtown Cleveland was boarded up by Wednesday morning, June 3, 2020 after protests Saturday over the death of George Floyd while in police custody in Minneapolis turned violent.Steven Litt, Cleveland.com

The violence spread to lower Euclid Avenue and East 4th Street, the entertainment district that links Public Square and the downtown business core to the Gateway sports complex, where the Cavaliers and Indians play.

But while broken glass can be replaced and downtown may recover, the coronavirus pandemic poses a serious long-term financial threat to the city as a whole.

Under Ohio law, employees could have income tax liability at home where they work remotely, not in the city where their employer is based. Cleveland could therefore be required this year to refund taxes collected from remote workers.

The losses could be devastating for the city, which expects to collect 85% of nearly $445 million in income taxes this year from remote workers who would be commuting in from suburbs, if not for the pandemic.

Such losses would come after decades in which Cleveland and Cuyahoga County have been bleeding jobs and taxes to outlying communities and counties, thanks to job sprawl and development of majority white suburbs enabled by interstate highways.

Viewed from this perspective, the pandemic could exacerbate systemic inequities that already pervade in Northeast Ohio, rendering Cleveland even less able to address entrenched poverty.

Solutions need to be sought at the regional scale, not just within the city and its neighborhoods. But Northeast Ohio and the state as a whole have resisted this kind of thinking, articulated in 2014 in the Vibrant Neo 2040 vision for Northeast Ohio. The project called for redeveloping the region’s aging urban centers and putting the brakes on new outward growth

The Vibrant NEO 2040 vision calls for focusing new development in areas of Northeast Ohio that are already built-up, plus preserving open land, and building a T-shaped system of transit lines along Lake Erie, and from Cleveland to Akron and Canton.Courtesy Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, Vibrant NEO

At bottom, the regional economy would be stronger, and suburbanites would live in a fairer, wealthier and more just society if low-income blacks were able to participate fully in the economy.

For Khrys Shefton, director of real estate for Famicos Foundation, the development corporation serving Hough and Glenville, the answer lies in whether whites in power remove barriers that prevent black households from accumulating and transferring wealth.

One starting point in urban development could include providing easier access to lending for minority-owned businesses, or enabling black developers to gain stakes in local projects.

“That’s what’s going to change generational wealth in the city,” Shefton said. “There’s nothing that black people can do about this,’’ she said. “Only white people can fix it.”

America’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, from stay-at-home orders to social distancing, shows that systemic change is possible. But that kind of mobilization has never been focused on eradicating racial injustice, Shefton said.

George Floyd’s death could be a turning point. If it isn’t, Cleveland will simply clean up again after the next uprising and the pain of the past 500 years will continue as if nothing has happened.